As mentioned above, gorillas are primates – so are other apes, monkeys, lemurs and humans (that’s right everyone, these are our RELATIVES and science has the DNA to prove it). There are many, many different species of primates and different classifications within that large group, definitely way too many to discuss in this blog. The one distinction I will make, because it is a mistake I hear often, is this: gorillas are not monkeys. Gorillas are classified as ‘great apes’ along with orangutans, chimpanzees and bonobos (pygmy chimps). Not wanting to get too complex here I will simply say that if the primate you are looking at does not have a tail, it is an ape. If it has a tail, it’s a monkey or another kind of primate, like a lemur for example.

The largest of the great apes, an average male gorilla weighs around 193 kilos (425 pounds); females are about half the size. Males have powerful jaws, huge muscular arms with an impressive span of over 2 metres (7 feet) and are about 10 times stronger than a human. Gorillas live in family groups called troops that can range in size but usually consist of one adult male, several of his females and their offspring – and the bond in these families is very strong. A sexually mature male has silvery grey fur covering his back, hence the term ‘silverback’. It’s the silverback’s job to keep his troop safe, settle any group squabbles, and it is he alone that mates with the adult females in his family. But younger males may encroach on a silverback’s territory trying to mate with his females or trying to take over his family altogether. If it comes to blows these battles can be brutal but most males try things like posturing and displays of strength to intimidate each other in hopes of avoiding outright fighting.

Yet for all their strength and the occasional territory battle, these beautiful animals are incredibly quiet and peaceful. It only takes one look into their eyes and a few moments of study to see how similar they are to us – and it’s incredible. Amazingly, although they are the largest of the apes, they have a vegetarian diet. They eat fruit, vegetables, bamboo, thistles and other plants; occasionally they may eat some insects but that’s not a staple in their diet. They move throughout the day, constantly grazing in order to fuel their large bodies.

As with most animals, gorillas are divided into different sub-species. Western lowland, eastern lowland and mountain gorillas are likely the most familiar to you. Gorillas live in the rainforests of Central and West Africa, although the mountain gorilla lives in montane rainforests. Unfortunately, gorillas are critically endangered and total numbers are estimated somewhere between 120,000 - 125,000; mountain gorilla numbers are very low with only about 786 individuals. Rampant deforestation, mining and illegal hunting for their meat and trophies is pushing these incredible animals to the brink of extinction. There are many great conservation organizations working hard to save them. One you may have heard of is the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International, http://gorillafund.org/. It was Dr. Fossey who made it her life’s work to study mountain gorillas starting in 1966, and it is because of her (and those who have continued her work) that we know much of what we do today about these incredible apes.

Another great organization is The Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project. They work tirelessly with the very small remaining mountain gorilla population helping to keep them safe and healthy. Check out their website at http://gorilladoctors.org/, it has great information and there’s even a blog you can follow.

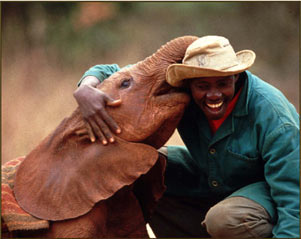

Returning to Tarzan for a moment, I think the reason I love the story so much is because it teaches us about compassion for other beings; Kala, a female ape loses her own baby and is devastated so when she finds Tarzan she adopts him, raises and loves him the same way she would have the baby she lost. The story teaches us to celebrate our similarities and not to focus on the things that make us different. We all need a family, a safe place to live, food, and water – as Phil Collins sings on Disney’s Tarzan soundtrack ‘we’re not so different at all.’ This is not only true of gorillas, but of all other beings and if we started to think about things in this context I believe the planet would be in better shape, definitely a kinder place to live. A little something to contemplate as you put your children to sleep and dream about their futures.